Want to incorporate morphology into your teaching? - Start here

You can incorporate morphology instruction into your program anytime you like. The only thing that holds teachers back is that they worry that they don’t know enough about morphemes and what they mean for spelling, word knowledge and complex subject-specific words – vocabulary. Trust me, nobody feels like they know enough! Just dive in and get going because morphology is a topic that gets kids interested, so you can learn along with them.

Says the Grade 1 teacher…

I teach phonics to my students pretty well and follow a program that introduces letter-sound correspondences in a structured, systematic way (to a sequence) but I want to build in morphology teaching. Even though we teach syllable division, many of our students are struggling to jump to two and three syllable words and I think an awareness of bases and affixes will help bridge the gap. How do I do this without stepping outside of the structure of the phonics program I’m using?

Says the Grade Seven teacher…

Our year sevens’ spelling results are concerning. We have a large number of students spelling phonetically and I think that morphology might be the missing piece that will help a number of them progress. I know that they’ll be using a laptop most of the time but we still feel an obligation to better teach them some of the basic spelling rules so they’re not constantly caught short with spelling.

Says the Grade Ten Science teacher…

Our year ten science students cannot remember the content specific terminology and this is seriously impacting their test results and holding them back. If we could work out a way to help them remember the vocabulary we could take them further and faster! The sciences are so full of words with Latin and Greek and we need to help our students better access these words.

Do any of these issues sound familiar? They are all situations where a focus on word morphology will unlock some doors to reading, spelling and conceptual understanding that would have otherwise remained locked to students. Schools who’ve chosen to go down the morphology rabbit hole have seen immediate benefits in student’s vocabulary, spelling, grammar and of course comprehension development. In this blog we will have a look at these teachers’ questions one by one and suggest where morphology can be built in.

I teach phonics to my Grade 1s pretty well and follow a program that introduces letter-sound correspondences in a structured, systematic way but I want to build in morphology teaching. Even though we teach syllable division, many of our students are struggling to jump to two and three syllable words and I think an awareness of bases and affixes will help bridge the gap. How do I do this without stepping outside of the structure of the phonics program I’m using?

Our grade 1 years teacher is right to feel some reservations about launching headlong into introducing his students to a set of common affixes (prefixes and suffixes) without first checking how this will fit with the phonics sequence. After all, it is the careful and ordered introduction of the code that makes sure we don’t overload students and have them revert to word guessing. Those days are thankfully long gone!

The answer at a glance seems quite simple! Only introduce affixes that contain the grapheme-phoneme correspondences (GPCs) that have been taught (so far) within the phonics program. However, there is more to this when the grammatical role of the affix is taken into account.

Let’s just start with selecting morphemes based on phonic code. Below is the Playberry-Laser Phonology scope and sequence for reception and year 1. It’s not unlike any other structured synthetic phonics sequence but it’s the one we use so we’ll use it to illustrate. Our grade ones have been exposed to the code from term 1 as well as all of the reception code. This means they’ve been taught, and practiced reading and writing with the following grapheme-phoneme correspondences (GPCs):

s (voiced and unvoiced), a (short), t, i (short), m, n, o (short), p, b, c, g (hard), h, d, e (short), f, v, k, l, r, u, j, w, z, x, y, ff, ll, ss, zz, ch, sh, th, qu, ng, nk, wh, ai, ay, ee, ea, oa, ow.

With this code our teacher should be okay to teach suffix ‘s‘ and ‘es‘ (see lesson plans for this in the member’s area of the Word Cracking website). Our teacher can also venture into suffix ‘ed‘ and suffix ‘ing‘. If we just go by phonic code then suffix ‘en‘ also looks good to go BUT the teacher will need to teach students about the job of suffix ‘en’ – how it forms intransitive and transitive verbs from adjectives (sharp to sharpen)! Did you hear the screeching of the tyres as things just ground to a halt? I’ve never taught year ones about transitive and intransitive verbs. So it’s not as simple as just going by the phonic code!

While on this functional level of suffixes, let’s walk it back and look at the simple suffixes ‘s’ and ‘es’. To work with these, students should already know about nouns (singular and plural) and what a suffix is. To deal with suffix ‘ing’, students need to have been taught about present tense verbs.

There’s a lot of grammatical understanding and new vocabulary needed to work with these suffixes. Until these concepts are explicitly taught, the teacher shouldn’t be expecting students to be independently reading or spelling words containing them. Sure, they can be exposed to words with these affixes in texts read to them by an adult, or in read-alouds, but in the spirit of teaching first, we need to explicitly teach all this content. Sorry suffix ‘en’, even though the students know your phonic code, you’re out for the time being! Our eager students will need to wait until term 2 for suffixes ‘ed’, ‘er’ and prefixes ‘un’ ‘re’ because they will need to have been taught open and closed syllables to deal with those prefixes.

If you’re thinking that our grade one teacher would benefit from a morphology scope and sequence to align with their phonics scope and sequence then you’re right! Suffixes and prefixes aren’t as simple as the phonic code within them. They are discrete units of meaning and they all change what a word does or means. This means that we need to be strategic and purposeful about the manner in which we teach them to students. A morphology scope and sequence that aligns with our phonics scope and sequence is going to be essential for our teacher (unless they have a linguistics degree). It’s lucky we have one for you!

So if you were wondering when suffix ‘en’ will finally get it’s day, it will need to wait for grade 5 term 4 in the Playberry-Laser Morphology Scope and Sequence!

How can morphology lift the spelling results for my year seven students?

Spelling is obviously more than just morphology. It’s a complex interplay between phonology (the sound structure of words) and orthography (the art of writing words with the correct letters according to standard usage). Strong spellers easily pull spoken words apart into their units of sound (phonemes) and then select the correct graphemes (individual letters or strings of letters) to spell those phonemes. They can choose from a vast array of possible spellings for a particular sound, or group of sounds and be able to process (consciously or unconsciously) all sorts of contributing factors like the type of syllable, a spelling convention (rule) at play, or an exception to that common convention that occurs in words borrowed from other languages. Strong spellers are using a reliable mental system that cross references between all sorts of stored information about the possible spellings of a word and more often than not, selects correctly. If you watch a spelling bee, contestants will often ask for a word’s language of origin, its part in speech, and its definition to help them choose a correct spelling of a word to assist in this mental cross referencing.

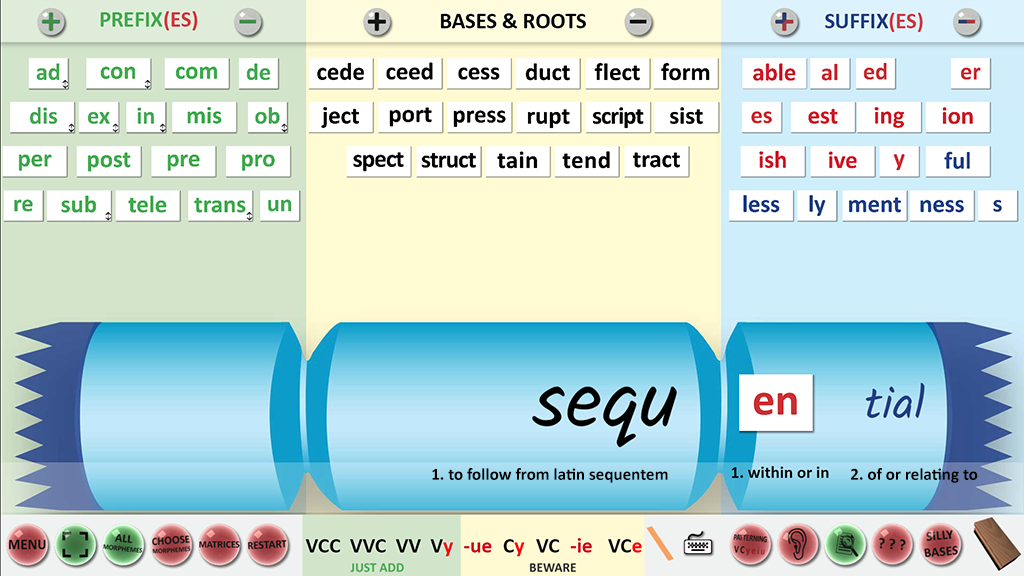

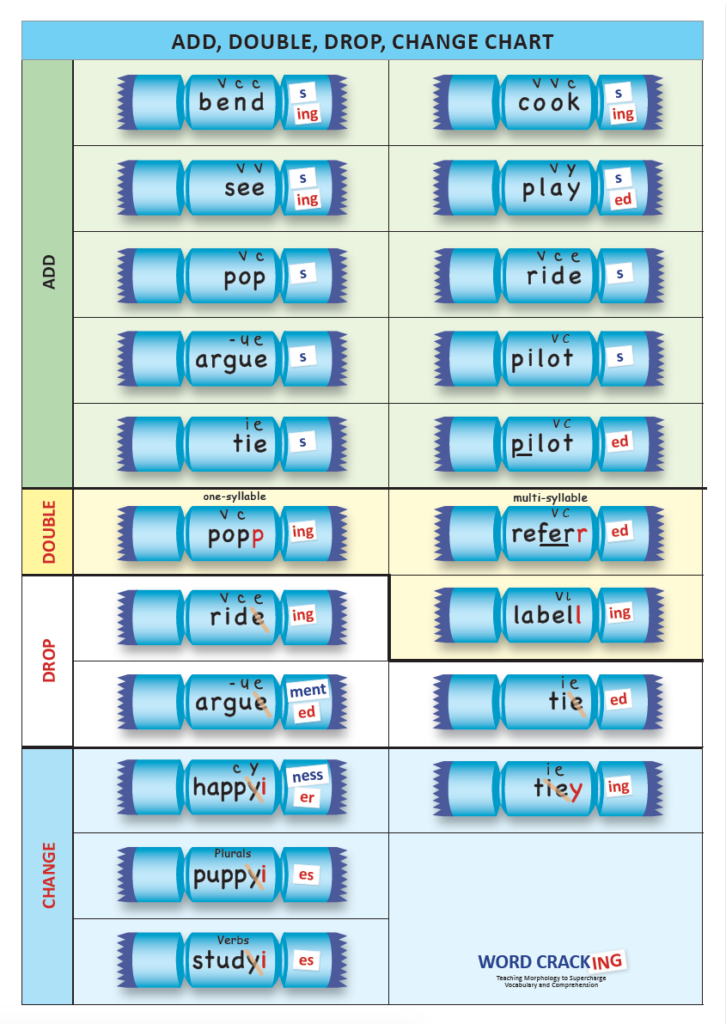

The Add, Double, Drop, Change chart contains examples of how and when to apply the big three spelling rules. The Online Word Cracker has handy settings that show students when these spelling rules need to be applied.

Our year seven teacher is noticing many students who in spite of being able to pick a spelling of a word that is phonologically sound, are misspelling meny more complecks words that reqier a hire level of understanding of syllabel tipes, speling conventshuns and are spelling many words in a way that demonstratees that they have littel to no awarrness that they compries of bases, roots, prefickses and sufickses. These students are stuck somewhere in the phonetic/transitional stages of spelling development. Explicitly teaching morphology to these students will be an important intervention. Poor middle school spellers (as long as their phonology is sound) also benefit from being taught basic spelling rules, long vowel choices and syllable types.

Developing a hypothesis about which spelling patterns and conventions are weak from a writing sample or spelling-age assessment requires a trained eye. There are some good diagnostic spelling tests that can help teachers to see where spelling weaknesses lie. In Word Cracking we use a set of diagnostic dictations to see how students are working with the spelling rules related to how suffixes add to words. These diagnostic dictations check the use of the double, drop and change spelling rules (aka the big 3 spelling rules) as well as some other basic suffixing spelling conventions. Administering a diagnostic dictation might be a good place to begin, along with using a normed spelling assessment to get spelling age data for students so progress can be monitored. Below is a summary of the seven diagnostic dictations in the Word Cracking Manual . The teacher can then either tailor spelling instruction for the entire cohort (wave 1), or use this information to inform intervention lessons. There is nothing to lose and everything to gain from incorporating morphology instruction into a spelling program, whether it be for all students, or at an intervention level. Middle school students get a real kick out of word study at the level of morphology as it takes spelling beyond basic memory tricks for trying to remember a string of letters and engages deeper knowledge about a word’s usage and origins.

Diagnostic dictations

Dictation

Checking use of

1. Lunch Boxes

use of suffixes ‘s’ and ‘es’ (just add rule)

suffixes ‘s’ and ‘es’

2. Camping

use of suffix ‘ing’ (just add)

suffixes ‘s’ and ‘es’

3. Walking to School

use of the add ‘k’ rule

suffixes ‘s’,‘ es’ and ‘ing’ (just add)

4. Shifting House

use of the doubling rule

suffixes ‘s’,‘ es’ and ‘ing’ (just add) and add ‘k’ rule

5. The Challenge of the Fittest

use of the drop ‘e’ rule

suffixes ‘s’,‘ es’ and ‘ing’ (just add), add ‘k’ rule and doubling rule

6. The Argument

adding suffixes to –ue endings rule

suffixes ‘s’, ‘es’ and ‘ing’ (just add), add ‘k’ rule, doubling rule and drop ‘e’ rule

use of the change ‘y’ to ‘i’ rule

suffixes ‘s’, ‘es’ and ‘ing’ (just add), add ‘k’ rule, doubling rule, drop ‘e’ rule and adding suffixes to –ue endings

How can morphology help secondary science students do better?

Talk with any student who feels disgruntled with science as a subject, and they will tell you the number one reason they don’t like science is all the new words they have to memorise. Students living with specific learning difficulties can find the recognition of these words in print, and their spelling, a barrier to learning the content. Maths teachers of all grade levels will tell you that students often confuse mathematical terms like perimeter and area and the cognitive load created by not having immediate access to the meanings of these words can impede their mathematical processing.

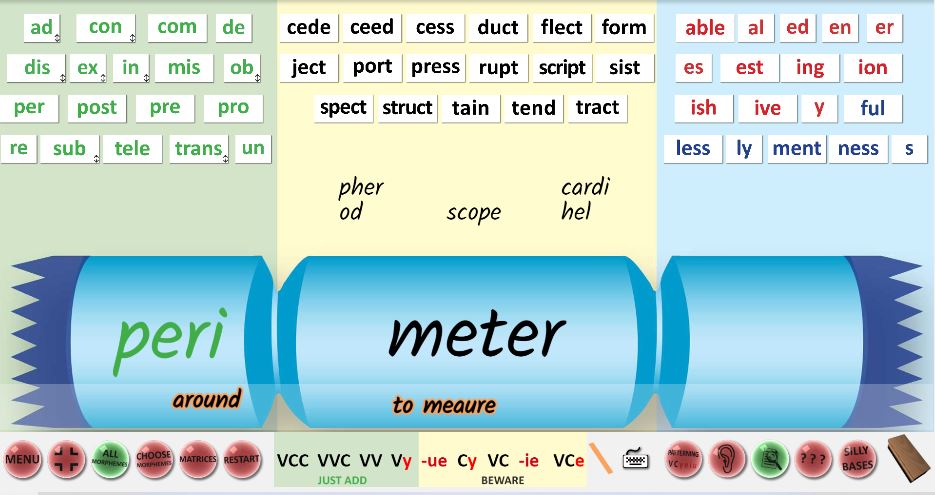

So, what if the next time you are working with perimeter in maths, you fire up Word Cracker and spend some time talking about the Greek prefix ‘peri’ and how this means around. Then you provide some images of other words containing ‘peri’ and briefly talk about their meaning and what ‘peri’ means in that particular word? The bang for buck will be enormous for the small amount of time you might spend doing this. The chance that you would have to re-teach what ‘perimeter’ means would be much slimmer. You’d also be doing the student a great service for when they encountered words like periphery, pericarditis and periscope.

morpheme: gen

Greek root meaning born, produced or origin

gene, genetics, gender, carcinogen…

morpheme: ign

Latin root meaning fire or burn

ignite, ignition, igneous, gelignite…

morpheme: lumin

Greek root meaning light or brightness

illuminate, luminous, lumen…

morpheme: iatr

Greek prefix meaning to heal or medicine

psychiatrist, geriatric, podiatrist…

morpheme: co

Latin prefix meaning with, joint, jointly or together

coagulate, cooperate, coefficient…

morpheme: hydr-o-

Greek root meaning water

hydrogen, hydrate, hydrant…

morpheme: peri

Greek prefix meaning about, around

perimeter, periscope, pericardium…

morpheme: voc

Latin root meaning to call

provoke, vocation, vocabulary…

morpheme: tain

Latin root meaning to hold

contain, retain, entertain…

A quick building of ‘perimeter‘ on the Word Cracker clearly shows its two morphemes at work coming together to mean to measure around. This quick activity significantly lowers the chance of students confusing perimeter with area.

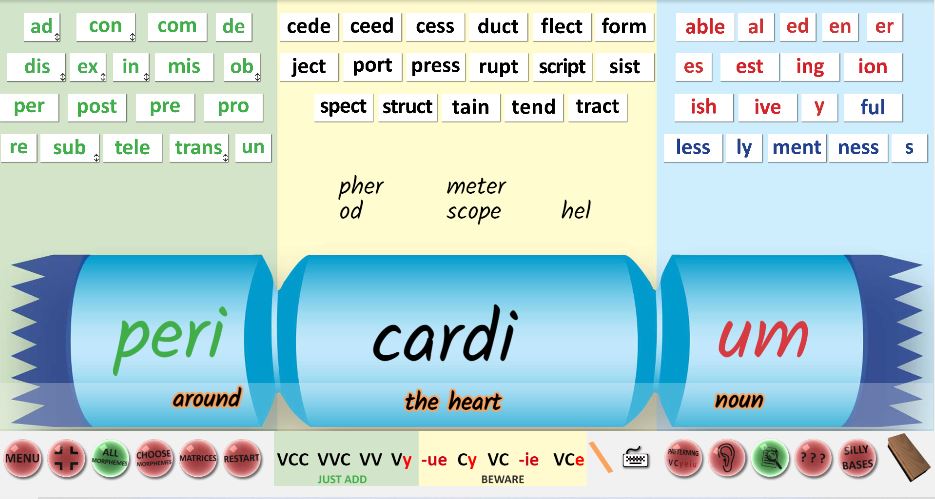

A quick building of ‘pericardium‘ on the Word Cracker shows its three morphemes at work coming together to form a noun meaning to around the heart.

A quick building of ‘periscope‘ on the Word Cracker clearly shows its two morphemes at work coming together to mean to look around.

Pick your words carefully

So get cracking!

I hope that this blog post emboldens you to dive in, despite any reluctance you might have about teaching morphology. Will you make some mistakes? Absolutely. I do all the time because morphology isn’t always straight forward. Remember though, looking at morphemes in a word with students, even if you are not entirely certain about what its morphemes are, still reinforces an incredibly powerful form of word study that can only help and will never hinder students’ word analysis skills. Importantly, it will also help them remember new vocabulary, consolidate spelling conventions and aid their understanding. So, get cracking and before you know it, you’ll surprise yourself with your own quickly growing knowledge.